On June 26, 2023, IBM announced its intention to acquire IT Financial Management vendor Apptio for 4.6 billion dollars. This acquisition is intended to support IBM’s ability to support IT automation and business value documentation. With this acquisition comes the big question: is this acquisition good for IBM and Apptio customers? Who benefits most from this acquisition?

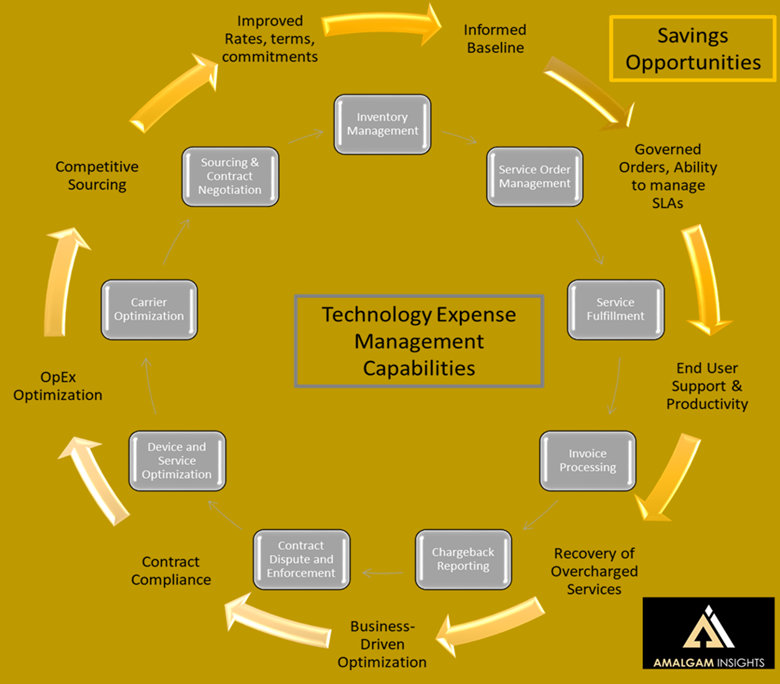

As an industry analyst who has covered the IT expense management space and first coined the Technology Expense Management and Technology Lifecycle Management terms as evolutions of the IT Asset Management and Telecom Expense Management markets, I’ve been looking at these markets and vendors for the past 15 years. In that time, IBM has gone through a variety of investments in the Technology Lifecycle Management space to manage the assets, projects, and costs associated with IT environments and Apptio has evolved from a nascent startup to a market leader.

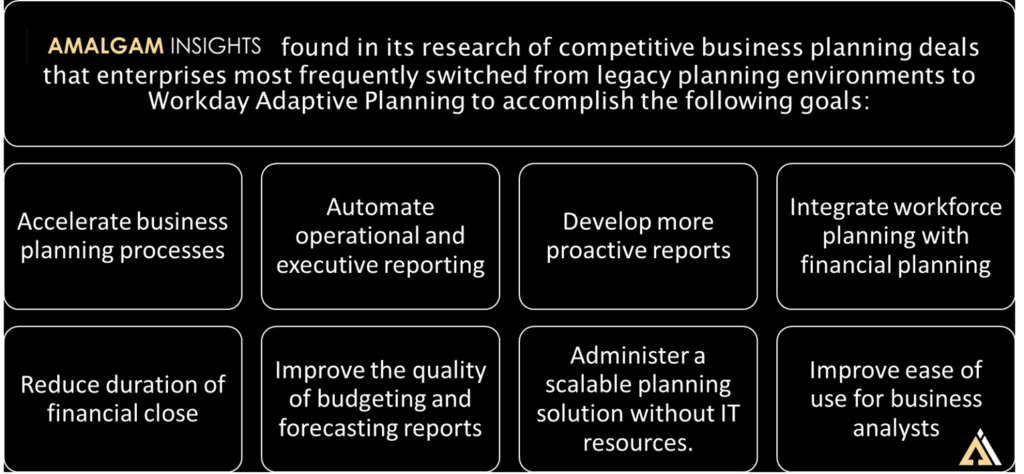

When Amalgam Insights is asked “What do you think of IBM’s acquisition of Apptio,” this opinion requires exploring the back story and starting points for consideration as there is much more to this acquisition than simply stating that this is “good” or “bad.” Apptio is a market-leading vendor across IT financial management, SaaS Management, Cloud Cost Management (where Apptio is a current Amalgam Insights Distinguished Vendor), and Project Management. But there is a multi-decade history leading up to this acquisition, including both IBM’s pursuit of Technology Lifecycle Management solutions and Apptio’s long road to becoming a market leader in IT financial management.

Contextualizing the Acquisition

To understand this acquisition in its full context, let’s explore a partial timeline of the IBM, IBM partner, and Apptio journeys to get to this point:

1996 – IBM purchases Tivoli Systems for $743 million (approximately $1.4 billion in 2023 dollars) to substantially enter the IT asset management and monitoring business. Tivoli goes to become a market standard for IT asset management.

2002 – IBM acquires Rational Software for $2.1 billion to support software development and monitoring.

2007 – Apptio is founded as an IT financial management solution to support the planning, budgeting, and forecasting needs of CIOs and CFOs seeking to better understand their holistic IT ecosystem. At the time, it is seen as a niche capability compared to Tivoli’s broad set of functionalities but is still seen as promising enough to attract Andreessen Horowitz’ attention as their first investment back in 2009.

February 2012 – IBM acquires Emptoris, which includes a leading telecom expense management called Rivermine, to support sourcing, inventory management, and supply chain management as part of its Smarter Commerce initiative.

May 2015 – IBM Divests Rivermine operations, selling off the technology expense management business unit to Tangoe. Tangoe uses the customization of the Rivermine platform to support complex IT expense and payment management environments for large enterprises.

November 2015 – IBM acquires Gravitant, a hybrid cloud brokerage solution used to help companies to purchase cloud computing services across cloud environments. Later renamed IBM Cloud Brokerage, this capability was intended to support IBM’s Global Technology Services unit in supporting multi-cloud and complex enterprise hybrid cloud environments. This acquisition logic ended up being accurate in the long run, but was too early considering that the multi-cloud era is really only beginning now in the 2020s.

December 2018 – HCL purchases a variety of IBM software products for $1.8 billion, including Appscan and BigFix. Although these Rational and Tivoli products provided enterprise value for many years, they eventually became outdated and seen as legacy monitoring products.

January 2019 – Apptio is acquired by Vista Equity Partners for $1.94 billion. At the time, I thought this was a bargain even though it was a 53% premium to the trading price at the time. At the time, Apptio had gone through a rapid stock price fall due to some public market overreaction and Vista Equity came in with a strong offering that pleased institutional investors. With investments in IT and financial software companies including Bettercloud, JAMF, Trintech, and Vena, Vista Equity was seen as an experienced buyer capable of providing value to Apptio.

May 2019 – Apptio acquires Cloudability, entering the cloud cost management or Cloud FinOps (Financial Operations) space. With this acquisition, Apptio answered one of my long-time criticisms of the vendor, that it did not directly manage IT spend after holding out on directly managing a trillion dollars of enterprise telecom, network, and mobility spend. This transaction put visibility to $9 billion in multi-cloud spend across the Big 3 providers under Apptio’s supervision while maintaining Apptio’s vendor-neutral approach to IT finances.

December 2020 – IT Asset Management vendor Flexera is acquired by private equity firm Thoma Bravo. Over the next couple of years, Flexera develops a strong relationship with IBM to support IT Asset Management.

December 2020 – IBM acquires Instana to support observability and Application Performance Management. As real-time continuity, remediation, and observability have become increasingly important for monitoring the health of enterprise IT, this acquisition provides a crucial granular perspective for IBM clients.

February 2021 – Apptio acquires Targetprocess to support agile product and portfolio management. The ability to plan and budget projects and products allows Apptio to support IT at a more granular, contingent, and business-contextual level.

June 2021 – IBM acquires Turbonomic, an application resource, network performance, and cloud resource management solution. With this acquisition, IBM enters the FinOps space. In our 2022 Cloud Cost and Optimization SmartList, we listed IBM Turbonomic as a Distinguished Vendor noting that it focused “on application performance” and that the “software learns from organizations’ actions, so recommendations improve over time.”

October 2022 – Flexera One with IBM Observability aggregates cloud spend across multiple clouds. This offering combined with Flexera One’s status as an IBM partner gives IBM customers an option for multi-cloud spend management and the ability to purchase cost optimization based on cloud spend.

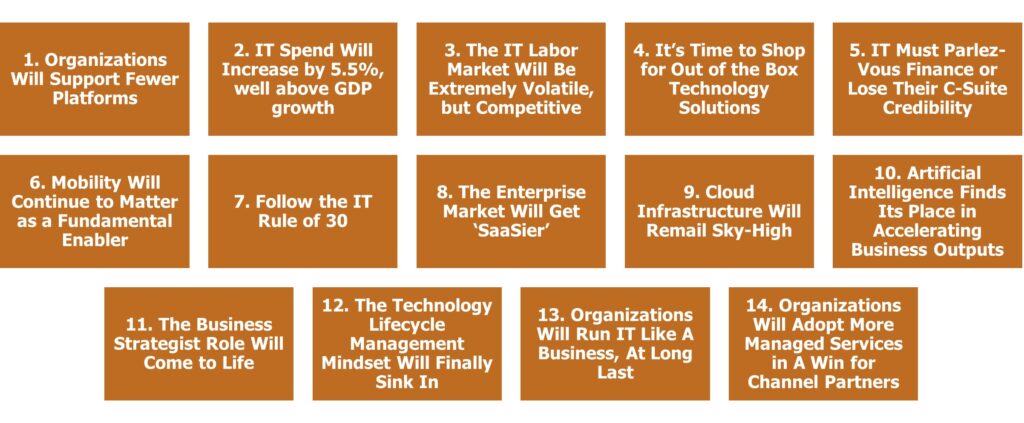

June 2023 – We come back to the present day, when IBM has agreed to purchase Apptio. So, now we are seeing a trend where IBM has invested in IT management solutions over the past couple of decades but has struggled to maintain market-leading status in those applications over time for a variety of reasons: market timing, market shifts, strategic positioning.

Concerns and Considerations

What is happening here? The problem isn’t that IBM is targeting bad companies, as IBM has consistently chosen top-tier companies and strong enterprise-grade solutions. This trend continues with Apptio, which has managed over 450 billion dollars in IT spend and provides a statistically significant lens for IT spend trends across a wide variety of vertical trends and geographies. From an acquisition perspective, Apptio makes perfect sense as a market leading solution executing on sales, marketing, and targeted inorganic growth to provide financial visibility and operational automation across global IT departments.

And the problem is not a lack of interest, as IBM has consistently targeted IT sourcing, expense, and performance management solutions with some success. IBM usually knows what it is trying to accomplish in purchasing solutions (with the exception of the missed Rivermine opportunity) and has done a good job of identifying where it needs to go next. As an example, IBM was early, perhaps too early, in pursuing multi-cloud brokerage services but in retrospect there is no doubt that multi-cloud management was the future of IT.

Based on my long market perspective of the Technology Lifecycle Management market, I think IBM has run into two main issues in this market: market size and partnership opportunities.

First, look at market size. This Technology Lifecycle Management market simply has not traditionally been an extremely large multi-billion dollar market on the scale of analytics, mainframes, or services. ITFM and related IT cost management services will always struggle to be much larger than a couple of billion dollars in revenue, as proven by market leaders across IT finance and cost such as Apptio, Tangoe, Calero, Zylo, Cass Information Systems, Flexera, Snow Software, CloudHealth (now VMware Aria), and Spot by NetApp. All of these solutions have grown to the point of managing billions of dollars, but none of these standalone businesses or business units have come close to reaching a billion dollars in annual recurring revenue. This is not an issue, other than that it is traditionally hard for behemoth global enterprises with $100 billion+ in annual revenue expectations to be fully committed to businesses of this size without trying to turn them into “larger” solutions that often lose focus.

A second issue is that IBM has a lot of internal pressure to play nicely with partners. The recent Flexera One partnership announcements are a good example where Flexera has quickly emerged as a strong partner to support IT asset management and multi-cloud cost management challenges and now will have to be rationalized in context of the capabilities that Apptio brings to market once this acquisition is completed. But when IBM has made commitments and plans to build significant services practices around a large partnership, it can be difficult to shift away from those plans no matter how significant the acquisition is. The challenge here is that even if the direct software revenue may pale in comparison to the services wrapped around it, the service revenue is still dependent on the quality of software used to provide services.

And despite any internal concerns about these issues, this is not a deal that Apptio and Vista Equity could refuse. The basic math here of adding $2.66 billion in market value in 4 and a half years, or roughly $600 million per year (minus the cost of acquisitions) is a no-brainer decision. Anyone who did not seriously consider this transaction would be considered negligent.

In addition, there are good reasons for Apptio to join a larger organization. There are limits to the organic development that Apptio can pursue across the Technology Lifecycle Management cycle across sourcing, observability, contingent resources and services, continuity planning, and MACH (Microservices, APIs, Cloud-Native, Headless) architecture support compared to what IBM (including Red Hat OpenShift and IBM Consulting) can provide. And IBM is obviously still a core provider when it comes to global IT support with a vested interest in helping global enterprises and highly regulated organizations with their IT planning capabilities.

Recommendations

So, what does this mean for IBM and Apptio customers? This is a nuanced decision where every current client will have specific exceptions associated with the customization of their IT portfolio. But here are some general starting points that we are providing as guidelines to consider this transaction.

For IBM: this is an acquisition where IBM is making a good decision, but success is not guaranteed just because of choosing the right vendor in the right space. There will be additional work needed to rationalize Apptio’s portfolio in light of how Turbonomic goes to market and how the Flexera One partnership is currently structured, just as a starting point. Amalgam Insights hopes that Apptio will be the umbrella brand for IT oversight in the near future as IBM Rational, IBM Tivoli, and IBM Lotus served as strong brands and focal points. IBM already has a variety of cloud and AIOps capabilities across Turbonomic, Instana, and Red Hat Openshift management tools for Apptio to serve both a FinOps and CloudOps hub as well as a strong go-to-market brand.

There is room for mutual success in this vision, as Flexera One’s ITAM capabilities are outside the scope of Apptio’s core concerns. This does likely mean that Flexera’s cloud cost capabilities will be shelved in favor of Apptio Cloudability and this needs to be a commitment. IBM needs to be a bit more greedy when it comes to supporting its direct software products than it traditionally has been over the last decade in maintaining the best-in-breed capabilities that Apptio is bringing to market, as the talent and vision of the current Apptio team is a significant portion of the value being acquired. IBM can be a challenging environment for software solutions, as every decision is seen through a multitude of lenses with the goal of finding some level of consensus across a variety of conflicting stakeholders. As this balance is sought, Amalgam Insights hopes that IBM focuses on building its direct software business and keeping Apptio’s finance, cost, and project management capabilities at a market-leadership level that will be championed by customers and analysts, even if this comes at the cost of growing partnerships. It can be easy for IBM software solutions to get the short shrift as its direct revenue can sometimes pale in comparison to larger services contracts, but the newest generation of IT to support new data stacks, hybrid cloud, and AI-enabled decisions and generative assets is in its infancy and IBM has acquired both solutions and a product and service team prepared to take this challenge head-on.

For Apptio: The past five years have been a strong validation of the continued opportunities that exist in IT Financial Management across hybrid cloud, software, and project management. There are still massive opportunities in contingent labor and traditional telecom and data center cost management markets as well as the opportunity to get more granular with API, transactional logs, and technological behavior that can be used to align the cost, budget, and health of the IT ecosystem. Amalgam Insights hopes that Apptio is treated similarly to Red Hat as a growth engine for the company and that Apptio has the operational flexibility to continue operating on its current path, but with more ambition matching the scale of IBM’s technology relationships and goals of solving the world’s biggest challenges.

For Apptio customers: You are working with a market leader in some area of IT finance or multi-vendor public cloud management and should hold fast on demands to retain the tech and support structure currently in place. As you move to IBM contractual terms, make sure that Apptio-related service terms, commitments, and responsibilities stay in place. This is an area where Amalgam Insights expects that the Technology Business Council will prove useful as a collective voice of executive demands to drive future Apptio development and evolution. Be aware that there are additional stakeholders at the table when it comes to the future of Apptio and it will be increasingly important for direct Apptio customers to maintain and increase demands in light of the increased complexity that will inevitably become part of the management of Apptio.

For IBM customers: You are likely already an Apptio customer based on Apptio’s current client base: there was a lot of overlap and synergy between the customer bases. But if not, this is a good time to evaluate Apptio as part of the overall IBM relationship as a dedicated solution for finance and cost management. In doing so, get IBM executive commitment regarding core features and functionality that will be strategically important for aligning IT activity to business growth. To deal with the cliches that every company is now a “software company” or a “data-driven company,” companies must have strong financial controls over the technology components that drive corporate change. At the same time, it is important to maintain a best-in-breed approach rather than be locked into an aging ERP-like experience as many companies experienced over the past decade.

These considerations are all a starting point for how to take action as IBM moves towards acquiring Apptio. Amalgam Insights expects there should be little to no concern with the acquisition moving forward as it is both mutually beneficial to all parties and lacks any sort of monopoly or antitrust issue that has slowed down larger acquisitions.

If you are seeking additional guidance to more granular aspects of considering Apptio, Flexera, IBM Turbonomic or other vendors in the IT finance, cloud FinOps, SaaS Management, or other related Technology Lifecycle Management topics, please feel free to contact Amalgam Insights to schedule an inquiry or to schedule briefing time.